Christian Villages on Lebanon-Syria Border Beef Up Security

Originally pulished in Al-Monitor

RAS BAALBEK and AL-QAA, Lebanon

Christian villages on the Lebanese border with Syria are increasing security, both militarily and on the civilian level, following death threats by a local municipality figure and reports of al-Qaeda-linked Islamist groups lurking in the mountains nearby.

“Civilians are forming patrols to protect the borders in places like al-Qaa and Ras Baalbek,” said a source in the Defense Ministry that chose to remain anonymous, as he wasn’t authorized to speak to the media. “What they are doing is in coordination with the local municipality and the governor of the Bekaa, so it’s half-legal, let’s say.”

The war in Syria has dragged on for almost three years now, producing so many casualties that the United Nations recently suspended counting at 100,000 dead. Despite Syria’s influence on its diminutive neighbor, Lebanon has only seen pockets of violence, occasional clashes usually limited to specific neighborhoods in Tripoli and increasingly regular car-bomb attacks. But with reports and occasional grainy videos trickling out of Syria depicting the brutal violence there, some of it sectarian, religious minorities in Lebanon are concerned by the threat posed from Islamist radicals working to establish an Islamic caliphate in Syria and beyond.

Ras Baalbek and al-Qaa are two of Lebanon’s largest Christian villages, inhabited predominately by Greek Catholics and located on the northeast border with Syria. To date, locals say Ras Baalbek has yet to experience any incidents involving armed groups. The Lebanese army is stationed at the village entrance and has conducted searches of the homes of Syrians who have recently taken up residence there. Despite the relative security, locals are still concerned with developments just across the border.

“After the kidnapping of the nuns in Maaloula, we are anxious and scared that maybe some of these radical groups will enter our village,” said William Nasr, a retired schoolteacher from Ras Baalbek. Many of the residents said that while such incidents have yet to occur, they don’t feel secure, considering their surroundings. In addition to the perceived threat in Syria, Ras Baalbek rests just north of the Sunni village of Arsal. In the last year or so, Arsal has become a bastion for fighters and a base for al-Qaeda-affiliated factions from which to operate freely and plan attacks in Lebanon.

“Since we are Christians, we are conscious of what is happening around us,” said Nasr. “We watch what is going on around the village with open eyes, though we don’t feel 100% safe.”

Though Ras Baalbek has seen little trouble, residents of neighboring al-Qaa feel the threat is more imminent. Numerous security incidents have already affected the village.

Al-Qaa Mayor Saadeh Hussein at-Towm said that in September, while celebrating a Christian religious holiday, he received notice of a threat from a militant wearing an explosive belt, intent on a suicide mission. The militant was captured by military intelligence before he could detonate his weapons.

This week, the head of al-Qaa municipality, Miled Rizk, claimed he received a death threat in a text message from a man purporting to be an Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) emir named Abou Hasan al-Mhaje. The emir said that rockets would rain down on al-Qaa if anyone from the village stood against his men.

Locals also say that some armed militants use the nightly fog to try to slip through the village. At the moment, residents say the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra is operating a kilometer away in the mountain range bordering al-Qaa.

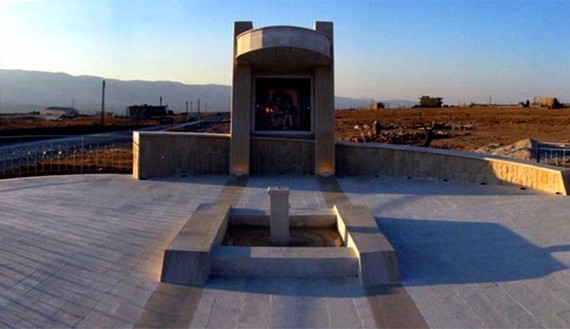

While al-Qaa is traditionally watched over by a large statue of the Virgin Mary, spiritual protection has been deemed insufficient, as the site is now acting as a makeshift base for around 125 members of the Lebanese Air Assault Regiment (AAR). The regiment’s troops, some of whom have necks the size of small tree trunks, are a strategic mobile reserve force that patrols the edges of the village in case armed militants trickle out of its wild mountainous backdrop. A unit from Lebanon’s internal security forces also guards the village, while Lebanese military intelligence is also monitoring the situation in both al-Qaa and Ras Baalbek.

In addition to the presence of the AAR and military intelligence, retired soldiers are forming units to patrol the villages.

“First of all, we are afraid of the brutality of radical Islamist groups like ISIS,” said Antoun Aad, a retired corporal with the Lebanese army from al-Qaa who has joined the civilian patrols. Aad, a burly man with thinning gray hair and a trimmed salt-and-pepper mustache, referred to incidents that attracted widespread media attention, including a video of a radical eating the heart of a dead enemy combatant.

“We share 40 kilometers (25 miles) of border with Syria and though the situation here [has been] relatively stable, it is collapsing around us,” said Aad.

About a year ago, while the unraveling of the situation in Syria continued, Aad and a group of other concerned retired military personnel decided to start patrolling their village, watching for armed insurgents.

“We recruited retired army soldiers to use them for protection,” said Towm. “We pay them for their gasoline, transportation and food, but that’s all. They still take their army pension.”

The group started with only five or six members but has grown to around 60 men. An average patrol consists of two cars with four retired soldiers in each, looking for any person or vehicle that looks suspicious or that they don’t recognize. They communicate using walkie-talkies and bought a private phone line that any resident can call to report suspicious activity. And while Towm says the patrols are not heavily armed, a message also conveyed by residents in Ras Baalbek, he maintains that the village has no shortage of weapons.

“Every one of us has a weapon, but we feel it is safest not to brandish them at the moment,” said Towm.

“We protect 90% of the village through our patrols,” said Aad. Still, much of the region remains out of the reach of the patrol units as security incidents continue to threaten the village. Earlier that day, two rockets had struck the mountains nearby.

Despite the Christians’ fears, some locals say that their role as minorities in the region works in their favor.

“It is not weapons that protect us,” said Butros Rizk, a former leader in Ras Baalbek’s Communist Party. “It is our wisdom and mind that can protect us. Everybody wants the Christians to be on their side.”

He added that even during the 15-year Lebanese civil war that pitted religious sects against one another, there were few incidents in the surrounding villages.

For most residents, though, fears persist as security incidents creep closer to home.

Wadiaa is an employee of the Ras Baalbek municipality and has lived in the village for all of her 50 years. She said, “We used to leave our doors open when we left the house, but now we lock them.

“Up until five years ago, I didn’t know that Arsal was Sunni, Hermel [north of Ras Baalbek] was Shiite or Zahle was Catholic, because we never had sectarianism,” she said, her voice betraying grave concern. “During the civil war, we didn’t feel anything. But we are feeling it hard now.”